I first heard Aimee Mann’s I’m With Stupid in grade ten. The year was 1996, the town: Burnie; the shop: Soundwaves Record Bar. I had just started my first job as a death-cook for KFC, earning my own money – albeit $4.70 an hour. I think two hours of slave labour may have covered the heavily discounted double fluro price tags on this particular Cee-Dee. (One cannot underestimate the victory of actually finding something you liked on special, given that the average album price was $31.50 – today’s equivalent of paying for six months of Spotify to hear the same ten Pearl Jam songs, one of them skipping.)

I’d only just gotten my first CD player, characteristically late to the go-go-gadget party. While other kids were playing NBA Jam on Mega Drive I had a second-hand Amstrad green screen with Bombjack loading on tape. On our modest pensioner budget I was the Piping Hot polar fleece to my best friend Billy’s Billabong jacket. Musically enforcing my insider/outsider status; while other boys were ensconced in Gunners and Green Day – I was investing in techno cassingles like Here’s Johnny and/or discounted quirky songstresses from LA.

Another plot-point in the meeting of the Mann’s was that it was only the previous year that the North-West coast of Tasmania had started receiving Triple J. (Pair this with the fact Burnie got MacDonalds in 1993 and you can begin to appreciate the colossal injection of excitement for a teenager in the back-sticks. If Tassie had scored its own AFL team maybe I’d’ve gotten the cultural trifecta.) Triple J had upgraded my stereo to that of ham radio. Via its social subscription I was a two-way team member of my generation, doors opening to reveal Jane Gazzo pied-pipering us through a bandwidth banner as my imagination ran onto the hallowed mainland astroturf of alternative anthems by King Missile, Faith No More and Cake. Romantically, I was single, yet my relationship with this cool cosmos community was a fascinating defacto funfest.

(I rang Calamity Jane up a few times, determined to tell her how I was going to break the school’s 50m freestyle record, that my nickname was Phonze and could she please play ‘Bentley’s gonna sort you out.’)

Justin (FRONT) probably only giving the thumbs up to air off some recent third-degree burn from the chicken vats or industrial ovens

Meanwhile, ‘Long Shot’ by Aimee Mann was on medium rotation. I can confirm this as I have a tape of it being back announced by Michael Tunn (admonishing the previous caller for ringing up from their mobile phone while on a domestic flight. “They say you shouldn’t ever do that”). There’s also an interview with Gibby from Butthole Surfers and a segment where callers phone in with the flaws they’d spotted in Independence Day. The whole thing couldn’t be more 1996 if Fran Drescher was covering Lump by Presidents sponsored by Stussy.

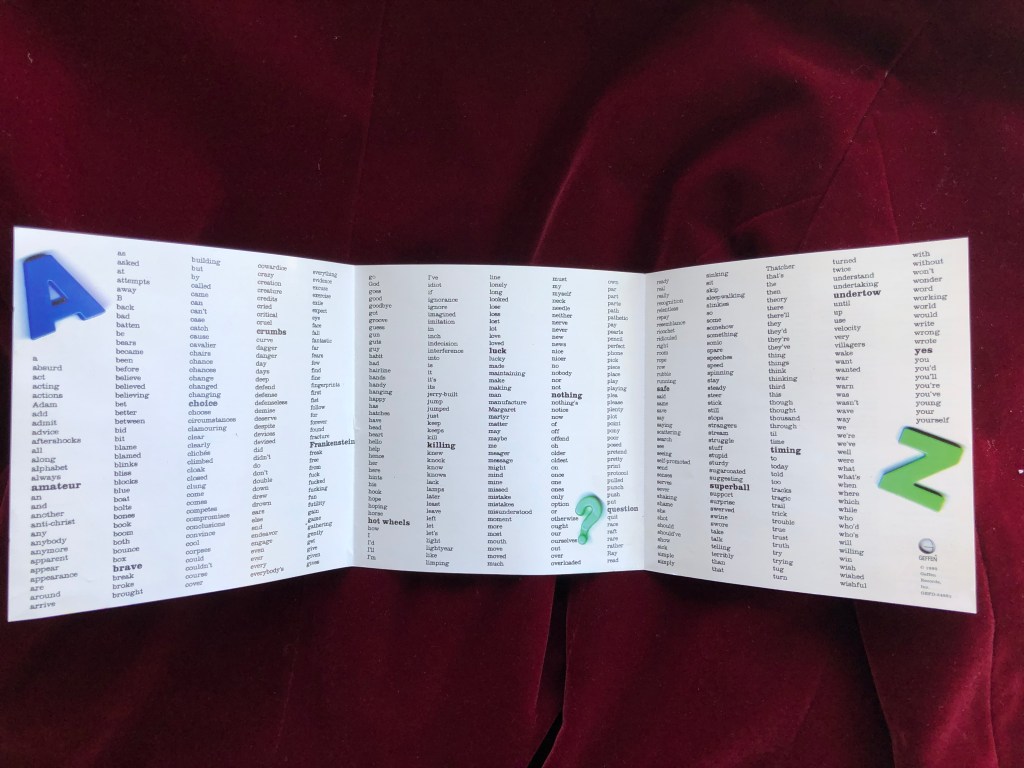

If anyone asks you if there’s a newfound nostalgia for CDs – the format we long swore we’d never feel anything but bemused, obligated indifference towards once the shiny holographic promise of their ‘unbreakable’ marketing gave way to the snake-oil-charlatan reality of two years wear resulting in every second song getting a remix by Fatboy Slim – backed with the retina-stretching liability of deciphering liner notes in 7-pt; the answer is a resounding, mid-life, bellowed into a pillow: “yes.”

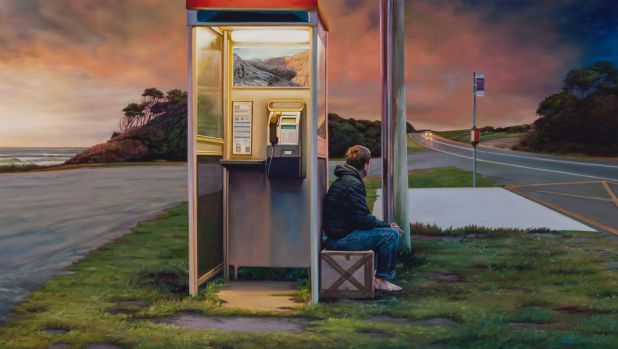

Yes, I played Long Shot, nay, BLARED IT in Surround Sound™ which my Sharp 3 CD changer afforded me, noting the spatial clarity compared to the head-under-the-bed compression of the Taped Off The Radio sound. Oh, to be sixteen again, plonked on the edge of your single mattress, pouring over the dynamic fridge magnet artwork and hazy artist portraits (all lyrics from I’m With Stupid are broken down into individual words and listed alphabetically)!

Hormones coursed through my gangly system like a technicolour forest of beauty and woe – crystallising my mood inside the lonesome wilderness of adolescence. Sparkly, intimate signals emanated from the padded black grills of the speaker box – entertainment as art absorbed in a halo of intelligence, curiosity and satisfaction. Beneath the alternative ambience of an after-school afternoon I afforded myself a double-value victory lap as my mechanical friend lurched the album around its carriage and back to the loading position. Helped by the odour of a Peter Jackson Super Mild smuggled out the window. I was revived and thriving, anything but alone in my teenage control room.

I was pleased to have a new inclusion in my modest CD collection, (comprising of RATM’s Evil Empire, Guru Josh’s Infinity, Spacehog’s Resident Alien, Butthole Surfer’s ‘Pepper’ single and Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Streets of Philadelphia’.) Aimee was my first musical girl. I knew nothing about her at all. I didn’t mind in the slightest. I was her prince silly, rescuing her from the discount bin in a small town that for multiple reasons hadn’t connected with her blend of Alternative pop-rock and whimsical lyrics about heartbreak and selfless relationships with damaged people – a theme it would take me another few years to fathom and two decades to perfect.

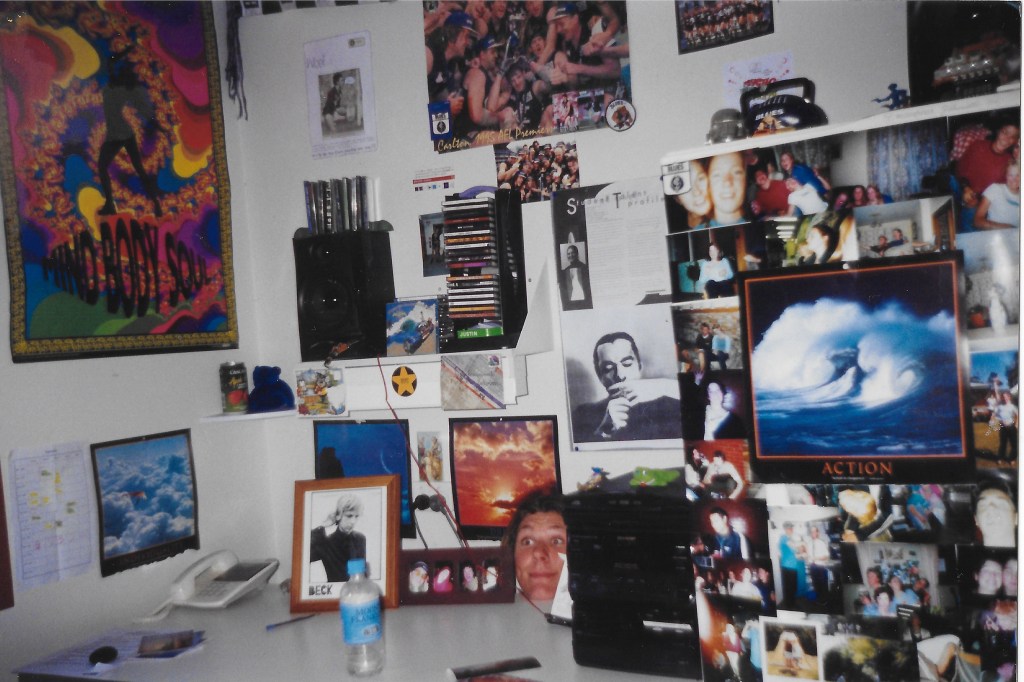

Justin’s very decked out room on residence at University of Canberra, 1999. You can make out the Sharp 3 CD changer and CD collection. I don’t know about you but I can also clock the timeless spines of Pearl Jam’s No Code, Beck’s Mellow Gold and George’s Holiday EP – err how did that get in there. Fair dues Holiday by George always has me tearing up. Is that tearing up, as in the healthy emotional response or tearing up as in tearing up my paper mache chain mail as I walk slowly backwards through IKEA? Much like what the chap says at the end of Radiohead’s Just, it’s best we never know.

In my first year at University in Canberra, my emotional world was blossoming outwards and inwards, not dissimilar to the flower motif depicted in Magnolia. Paul Thomas Anderson’s masterwork was a timely injection of Aimee Mann wonderment which sent the cultural value of I’m With Stupid climbing the rungs of my CD tower ahead of recent hotshots Garbage, Ben Folds Five and my failed experiment with Counting Crows. Released in 1999, Magnolia was the first real arthouse film to connect with my generation (that wasn’t Romeo & Juliet or Young Einstein.) Indeed, it was so good that it was actually hurting my new best friend Matt, literally depressed that he’d never make anything that good in his lifetime.

Aimee Mann’s song ‘Deathly’ single-handedly inspired the entire movie. If there’s a higher honour that has been paid a songwriter in recent times I’d be interested to hear about it. In the liner notes to the soundtrack Paul Thomas Anderson writes: “She is the great articulator of the biggest things we think about: ‘How can anyone love me?’ ‘Why the hell would anyone love me?’ and the old favourite ‘Why would I love anyone when all it means is torture?’”

It would make sense that a director would be drawn to Mann’s songs as they play like lyrical storyboards. There is a sense of narrative, of place. The language is visual and immediate. As PTA goes on to say “Aimee is a brilliant writer” and these are ‘story songs’ – which is perhaps a quality that could be dismissed as being a little, dare I say it, daggy. By that I mean to say that Aimee Mann’s compositions are disarmingly, wholesomely forthright when compared to contemporaries such as PJ Harvey or Tori Amos – fuelled by an edgier riot-grrl poetic abstraction.

That isn’t to say Aimee’s lyrics or compositions aren’t edgy. Any cabaret-esque over-spelling is under-written with smarm, juxtaposition and wit. S**t yes, Aimee Mann is witty! A rare quality in female artists that don’t toe-dip in pseudo-novelty such as Jill Sobule’s ‘I Kissed a Girl’ or Diana Anaid’s ‘I Go Off.’ Aimee’s an off-kilter, off-broadway eccentric, like Rufus Wainright or Suzanne Vega – or, more closely to my discographic heart; fellow LA misfit troubadour Eels.

Eels is also a bit ‘daggy’ in the indie-cool scheme of things, (Well, maybe I’m speaking out of school and drawing too much attention to my own internal crisis of confidence about what is relevant – but Pitchfork have slagged off most of his releases for being musically two-bit and lyrically hokey, which is code for ‘the kids aren’t comfortable with artists, (especially men) wearing their mentally ill minds on their sleeve and being intentionally vulnerable unless it’s done ‘authentically’ by a mentally unstable artist such as Daniel Johnston. Read: ‘If you’re going to be troubled, either strip it right back by singing your breakdown on a warbly acoustic, or, have the courtesy to dress naked lyrical honesty with full-tilt production al la Nine Inch Nails – self-pity is way too unpalatable to be presented as musically laid-back and self-aware as Eels does. Anyway, I disagress. (Disagreeing with my own digression.))

And, didn’t rage play Eels surprise new single only last week? (Oh good he’s going back to his Souljacker days.)

Pitchfork gave Aimee Mann’s complicated 2000 album (which she released independently after record labels were bamboozled by its lack of singles – who is she taking career advice from, Fiona Apple?) 9/10, so what would I know. Answer: heaps. Buy me a milo.

I’m told the case is now closed

So I can come to my senses

But when the question is posed

I’ll have this meagre defence

Aimee’s songs are riddled with metaphor. Everything’s a set up. Love as a heist, relationships as a court case, boyfriend as a fallen superhero. There are twists on words. Plays on devices. Ducking and weaving and jabbing and hooking – Mann is the lyrical shadow boxer – floating like a butterfly tattoo and stinging like a worker bee.

As Paul Thomas Anderson pontificates: “She writes lines that are so simple and direct, you are convinced that you have either A) heard it before B) said it before, or even C) thought of it before (and just never wrote it down).”

I was hoping you’d know better / I was hoping but you’re an amateur

Songs are mostly about breakups. Odes to the calamity men who’ve wooed and screwed her every which way to dinnertime. I read that she had battled depression – there is a defiant dramatic tension that offsets any long stays on glib island.

I’m a superball / If you bounce me once I’ll ricochet / Around the room

So row, row, row your boat gently down the stream / I hope you drown and never come back

Anger marinated in eccentricity basted with irony. This recipe sets Mann apart from her contemporaries such as Sheryl Crow or Alanis “irony” Morissette. The lyrics are immediate, conversational and visual. Mouthfeel of the mind with heart aftertaste. They never drift or waft, rather announce and elucidate stakes of the highest order from a dulcet energy palate.

I’m so relentless / And you’re defenceless

Oh, and she rhymes her socks off. 🧦 Ms Mann’s like Dr Seuss meets Karen Carpenter.

You may wonder what the catch is / As we batten down the hatches

A double syllable rhyme worthy of Kim Carnes’ precocious / pro-blush.

But of course, the central thread that carries me from creation to memory and back is the voice. Aimee Mann owns my devotion through the gorgeous timbers of that velvet chamber.

And I don’t even know you / I don’t even know you anymore

She can hit the high-notes that fall you to the floor. She can glean the low-tone that floats your nose to the ozone. She whispers friendly and dangerous – truths disarmed in confident softness. Mann has approximately the best voice in history. Like none other in the canon. A god-standard Chrissie Hynde / Harry Nilsson masterclass in originality.

Hers is the vocal equivalent of a fresh pressed ruby velvet jacket. Sinking deep into a shady orange corduroy lounge, sipping an expensive bottle of French-Canadian merlot, reaching for a soft pack of Stuyvesants.

Comfort chords. Gold vibrations. Choc-coloured cotton socks.

An Aimee Mann album feels like a special occasion. No, I don’t listen to her regularly. (Perhaps the richness of her voice means that one becomes fuller, sooner.)

But when I return I am always uplifted, reminded, surprised.

I’m With Stupid was one of the last holdouts on Spotify – outlasting Bill Callahan and Beyonce. (Mysterious, as the rest of her catalogue was there.) I lost my original CD and recently purchased a new second-hand copy, for approximately the same amount I paid in ’96 – in some satisfying twist of capitalist consistency. I was mesmerised by how much more alive the songs sounded. My ears used more muscles; heard extra instruments. As my friend Conrad once said “CDs sound better than streaming, even burnt ones. It’s something about the preamps in stereos.”

That said, in my current station; no longer the new sensation and far from the legacy veteran, it would not be in my best interests to bore you with rhetorical implorations to go out and buy your first CD in like, 15 years. All I’ll say ROCK FANS, is that there’s never been a better time to revisit this obscure slice of mid 90s Alternative and find a comforting voice in these abrasive times.

Dig?

I saw Aimee play live in 2009. I’d heard she was notoriously shy and awkward, especially about banter between songs. So much so that she’d hired a comedian to act as MC at her US concerts. Over-compensating for this by a long-shot – she proceeded to jabber nervously for up to ten minutes while taking photos of the audience before playing a single note. I am churlishly in awe of my idols when it becomes obvious they are consistent in their vulnerability.

At the end of the set she was taking requests. I was too insular to yell but I would have requested Long Shot. It is still one of my favourite songs of the nineties – conspicuously absent from any themed playlist.

Whatever.

A. Mann

And the award for best swearing in the opening line of an album:

You fucked it up / You jumped the gun / I swore you off / but You climbed back on.

Aimee Mann does this bright/melancholy, sweet hook, minor chord-twist dark pop thing that just fucking kills me. In a good way. It’s weirdly too rare in rock music. Any band that can do this as good as Aimee Mann, you’ll make me emotionally crumble and feel like life’s beauty is indisputable.

Adam Gropman (via youtube)

Aimee Mann – I’m With Stupid (1995, Geffen)

Key tracks – Superball, Long Shot, Sugarcoated, Choice In The Matter.

RELATED READING (SMH Interview 2009)

Fun Fact: Aimee dipped her toe into acting by playing one of the German nihilists in The Big Lebowski. (Continuing her love affair with indie-darling directors).

Gigs: Aimee is touring Australia in 2021/22 with appropriate folk oddball Ben Lee!

Know something I don’t?

Keep it to yourself.

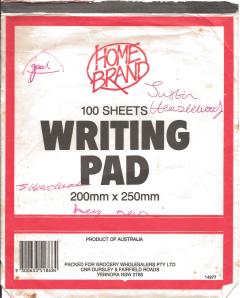

Justin’s CD inventory as catalogued by then girlfriend Tammy at their sharehouse ‘The TAJ’ (named after occupants Tammy, Adam and Justin) in Totterdell Street, Canberra, 2001.

A very 2001 looking, CD orientated sharehouse wall. Note the square metal CD holder display which I bought from a mail order catalogue in grade 12. BTW that is the Beatles poster I mention in Megan the Vegan. (CD display features Waikiki, Skunkhour, Supergrass, New Buffalo, Sleepy Jackson, Dandy Warhols, Divine Comedy, a fairly rare single from Radiohead’s Amnesiac and Starsailor!)

I guess you could say I have an intimate knowledge of indie releases from 2001 because of my job at the Uni magazine Curio. We were getting sent lots of review CDs and it kept me across awesome female singer-songwriter sneaker singles such as Airport ’99 by Phillippa Nihill of Underground Lovers and Like A Feather by Nikka Costa (one of Mark Ronson’s first hits as producer). Not to mention a promo copy of Aimee’s Bachelor No. 2 or, the Last Remains of the Dodo – now THAT’S how you title an album.

T H E E E N D E

READER SERVING SUGGESTION

Justin, hello, it’s reader here. I enjoyed your column about Aimee Mann.

Thanks!

You write in a very original, thoughtful manner. I remember my first CD by a female that I bought in my country town and there’s a great story about it. Shall I share it with you?

Please.

Where can I read more of your writing like this, in this style or whatever.

Oh, there’s the “MUSIC” tab under ‘Columns’ which has a few similar proto-pretentious fine-arts deep-drives. Or just keep scrolling down the page as I’ve recently gone on about the film Love Serenade and my love of synthesisers.

Okay, thanks Justin, I really appreciate you sharing your writing here on your website.

Thanks! I appreciate the feedback, even though there is no comments field because WWPD (what would Pitchfork do)?